Interlacustrine Victorians: Apollo Kaggwa

The Guardian recently reviewed an exhibition of photographs

of Africans made by the London Stereoscopic Company. This nice article inspired

me to start a series of posts with photographs from interlacustrine Africa, which

I haven mainly taken from C. W. Hattersley’s book “The Baganda at home”. I hope

I will add more sources to the project in future.

I take the

term “Victorians” in a very broad sense. To me it’s not only about British

culture in 19th century, but something that describes a global

colonial culture that spread with the European expansion. The “Victorian” in

this global colonial culture is a set of certain understandings about the

individuality, concepts of the family, the notion of education as a tool for

self-improvement and finally a set of habitual practices.

Why it is

global? Colonial expansion in the 19th century was a European

project. Sure, Britain was at the forefront of this endeavor, but it was not

the only party involved. Between the different European powers there were many cross-cultural

flows. Many Europeans from other nations, Asians and Africans worked in various

functions of Britain’s informal empire in Africa the three quarters of the 19th

century. Notably to the Germans,

Britain’s imperial culture served as a model for their own imperial habits.

Victorianism therefore was not confined to Great Britain. Other European too participated

in its spread around the world. So did Asians, Africans and Americans, too.

According to David

Cannadine, British imperial culture took much from its contact with Indian

elites.

Why its

colonial? The colonial expansion of Europe was a main track for the dissemination

of Victorian culture around the world. Many core concepts of Victorianism were

connected to Britain’s imperialism. Abolitionism

and liberalism nurtured its imperial desire. The importance of education for self-improvement

was a main pillar for missionary visions to convert Africans. Africans’ fascination for Victorian life-style was a

result of an increasing connectedness with global markets. Urban elites from

the Gold Coast, who had become rich trading within the Atlantic Ocean adopted parts

of Victorian cultures as a way to participate in an emerging global culture.

The adoption

of Victorian culture by these Gold Coast elites coincided with a new interest

in their African roots. Gold Coast intellectuals proudly wore African clothes,

searched for their own aancestry and history Patterns of Victorian culture were indeed only

one among other that fascinated Africans and served to express the social

change they experienced in the 19th century.

This was

the case with Apollo Kaggwa and the Bugandan elites, too. Kaggwa was, according

to his own testimony, born in 1865.[1]

This was a time, when Muslim traders from the East African coast became

influential at the court of kabaka Mutesa I. The kabaka himself showed a great

interest in the Muslim faith, Of much greater fascination were the luxury goods

the traders brought with them. The Bugandan elites enthusiastically adopted

coastal cloth and habits as a way to express their distinction toward

commoners. Kaggwa himself, who became member of the household of an important

chief, had some contacts with Bugandan Muslims. The caretaker of the Royal

Mosque, a certain Nzalambi, promoted him to the court of Mutesa, where he joined

the service of Kulugi, the chief keeper of the royal stores.[2]

Under the influence of missionaries of the Christian Mission for Africa, who

arrived in Buganda in 1879, Kaggwa later choose the Christian faith. He probably

did this for the same reason the

predecessor generation choose the Muslim faith. In the political turmoil that

followed Mwanga’s accession to the throne, Kaggwa was arrested in 1886. He was publicly

beaten, but escaped death. One year later the civil war in the Buganda started,

in which different faction of the elites fought for dominance. This was not

uncommon in Buganda’s political history, but this time the fight for power was charged

with religious confessions of the rival parties. Kaggwa became the leader of

the Protestant faction. As a result of a power sharing agreement with Mwanga,

he became for the first time the katikiro of Buganda, the highest office after the

king. Peace lasted only for a few months. With the help of Frederick Lugards

Imperial British East Africa Company, the Protestant faction first won over the

Muslim faction and later over its former allies, the Catholics. Mwanga went to

exile, and the minor Daudi Chwa was installed as a the new kabaka. As result,

Kaggwa became the most powerful man in Buganda. He played a decisive role in

Buganda’s path towards its inclusion into the British sphere of influence and,

more important, to a complete overhaul of its political and social life.

Being a

part of the British Empire meant to Kaggwa also becoming a Victorian. That was

as much a statement of acceptance of the Empire’s influence as a statement

about equality. The Bugandan agreement of 1900 assured the Bugandan elite a

large degree of autonomy. Buganda became part of the British empire as an ally

not as a subjugated enemy. This, at least, was the viewpoint of Bugandans like

Kaggwa. The British had a slightly different view and the struggle over the

interpretation of the Buganda agreement last for years.

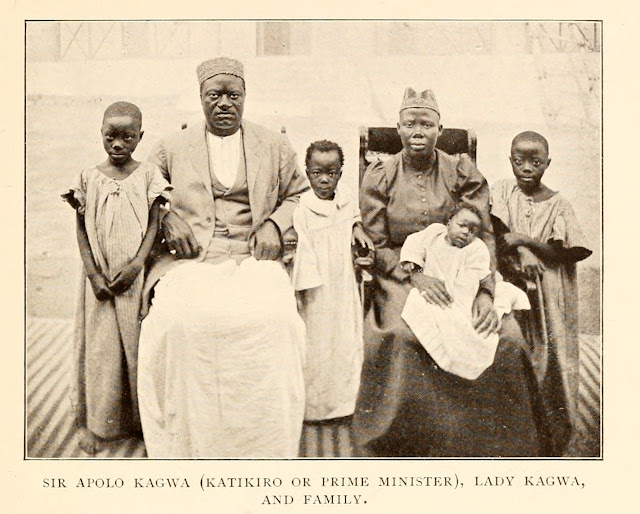

On the

photography, we see Kaggwa’s interpretation of Victorian culture. It is about Christian

norms of family, about self-confidence and individuality. But still, this

is mingled with traces of other cultural influences. His clothes still show the

influence of the Muslim coastal culture. Like the coastal intellectuals in early 19th

century, becoming a Victorian meant also developing an interest in its own

heritage. Kaggwa was one of the first Bugadans to explore the kingdom’s rich

history. He wrote several books on this topic.

Comments

Post a Comment