Landscape as the Radical Other

by Michel Keding

“And sunsets,

the African sunset is a must. It is always big, and red. There is always a big

sky. Wide empty spaces and game are critical – Africa is the Land of Wide Empty

Spaces”

- Binyavanga Wainaina: How to Write about

Africa

As Europeans

increasingly left their temperate homelands to allegedly discover new lands,

they found themselves in climates and vegetations unlike anything they had

known before. Ever since 1492, if not before that, adventurers, pioneers,

naturalists, (para-)ethnographers and other travellers tried to account these

marvels to their kinfolk in the form of stories, travel reports and of course,

visual imagery.

Unsurprisingly,

the dawn of photography and its ongoing improvement provided new means of

representing these other worlds as mass-consumable goods in school books, on

postcards, posters, in newspapers and other prints. As with anything alien,

these new landscapes were charged with notions of danger, exoticism, brute

force, but also outlandish beauty, untouched by spoils of civilization.

Scorching heat, colossal rainfall and humidity, dangerous animals and insects,

unknown diseases and of course, ostensibly primitive peoples formed part of the

experience of barren deserts or lush rainforests that grew gigantic trees,

colourful flowers with wondrous fruit and an almost impenetrable thicket.

These new

landscape became repositories and tokens of radical otherness, as it were,

constructed as inferior, savage, barbaric and/or noble, and essentially providing

that contrast agent that to date is so important for European identity.

Representation of landscape, and in particular photography, in this

understanding never was or is simple collection of data, or a snapshot of

reality, but is part and parcel of greater narratives that may said to be

selective, partial, charged etc., but certainly not representative, objective

or just to those that are being (mis-)represented.

The case of

photography is of particular interest here, as the close resemblance to the

visual experience makes consumers of this medium especially gullible. Photography

usually has quasi-scientific credibility, it is ‘photo-realistic’ and we (at

least us westerners), who emphasize and rely heavily on the visual in everyday

life, are so easily tricked into believing what is depicted. Arguably, in

present day there is a fairly common understanding that selection of frame,

digital editing technology and context are powerful means of tweaking the

effects of a photograph. Nonetheless, images stick in our memory, possibly more

than other sensual inputs, they resurface with related tropes and are potent

agents of reproducing distorted narratives on a cognitive level. This makes it

particularly crucial that photography is questioned, contextualized, picked

apart and criticized and that we unlearn to take it at face value.

Now, one could

ask, what is the relevance of colonial photography in what is generally

considered a post-colonial era? There are countless examples of continuities

between colonial and present-day representations which are quite present in our

everyday lives. We know the poster-children of charitable organizations that

feed the narrative of the suffering, helpless African, stripped of clothes and

agency, or the disneyfication of wildlife and noble savagery in The Lion Kind

or Tarzan or The Gods Must Be Crazy. Similarly, there are specific notions of

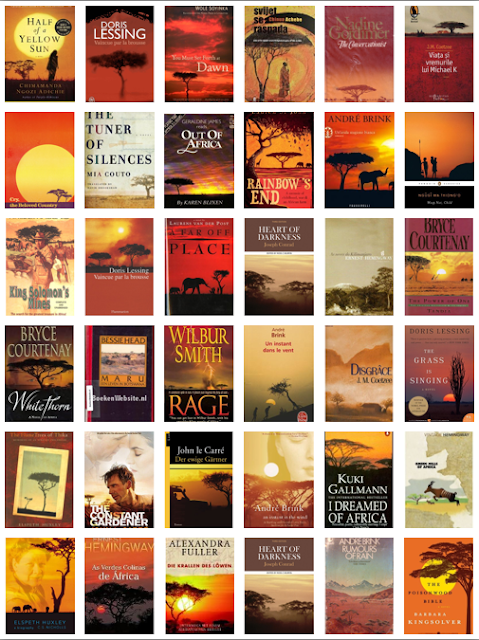

landscape tied to Africa that are easily recognizable. The above picture is an

assembly of cover images of books staged in Africa, which circles through

social media[1].

One quickly notices orange-red sunsets, usually an acacia tree, here and there wildlife.

Rarely people, with the exception of Ralph Fiennes, who portrays a White

Saviour in the film-adaption of The Constant Gardener.

What is it about

the savannah sunset that evokes “Africa!” at first sight? For one, as opposed

to the palm tree or rainforests, that particular landscape is not found

anywhere else, so it prevents confusion. Secondly, one might say it feeds into

a narrative of Africa as untouched, endless beauty, a place where giraffes and

elephants still walk off into the twilight. Thirdly, it resounds with a far too

common misconception, namely that Africa is a country.

This image is,

to my mind, the equivalent of The Noble Savage in landscape photography – close

to original nature, simple, yet elegant, untouched by the ‘side-effects’ of

so-called civilization. In that, it becomes a particular token, which stands

comfortably between other tokens that represent other strands of colonial and

western narratives on Africa, i.e. the brutal, the war-torn, the helpless, the

wretched. The short essay behind the above quote is a concise summary of

representations.

Understanding

the colonial legacy of these narratives is crucial in their deconstruction.

Therefore, cultivating a new, critical practice of remembrance of this past is

essential. Furthermore, we, as Europeans who have been socialized within these

tropes, have to always scrutinize the how and why of the representations we create,

be they science, knowledge, story or photography – because it is in that that

we have created the Other, and through the Other, we sought to distinguish our

Selves.

Comments

Post a Comment